Fat Chicks in SFF – Alis Franklin

One of the things I loved about this series last year was that it made me think. Each essay pointed out things I’d never considered, or helped me to get a better understanding of other people’s experiences. This year’s essays are no different.

In reading Alis Franklin‘s post, one of the things that stood out for me was a comment toward the end. She talks about how it’s easy not to think representation matters when you see yourself in so many stories that you don’t comprehend what it’s like to not see that reflection…but that it’s also easy to think it doesn’t matter when you never see yourself. Because your invisibility becomes “normal,” and it never even occurs to you that it could or should be any different.

I was in high school. I had glasses, dead-straight straw-brown hair with bangs a decade out of fashion, and a tendency to wear too-big tie-died t-shirts featuring screen prints of aliens and dragons. I was good at English, bad at Math, terrible at sport, and spent most lunchtimes playing games with colons in the name, like Magic: the Gathering and Werewolf: the Apocalypse.

In other words, it was the 90s, I was a nerd, and I knew I was never going to be a hero.

Don’t get me wrong. This latter realization wasn’t because of the bookishness, the bad fashion sense, or even my complete inability to run or catch or throw. It wasn’t because I had no friends. I had plenty (all the better to play TCGs and RPGs with). I wasn’t because I was bullied (I wasn’t), or didn’t date (I did).

It wasn’t even because I was a girl. Well, not really. At least, that was only half of it.

Because that’s the thing, isn’t it? I knew, at the tender age of thirteen, that I would never be a hero because I was a girl, and I was fat.

#

There are no fat chicks in SFF. And by “SFF” I’m including the broad tent of my teenage nerdish interests: sci-fi and fantasy novels and TV shows and films, yes. But also video games, comic books, trading card games, horror, urban fantasy, roleplaying games. The works. There might as well have been a great big NO FAT CHICKS sign hanging outside the entrance. And me, peering in through the flaps, loving the show but always knowing I would never, ever be it.

There are no fat chicks in SFF.

There are geeks, sure. Geeks a-plenty, and I loved the Willows and the Mizuno Amis as much as the next bookish loser. But Ami wore a sērā fuku and Willow cosplayed a vampire by putting on skintight leather pants. All it took was one look from that to my own chubby knees to realize that would never, ever be me. The geeks might inherit the Earth, but–for women, at least–they had to look hot while they did it.

(Years later, I found out about “fat Willow,” the version of the character that appeared in Buffy’s original pilot. By that stage, the fact that actress Riff Regan had been replaced by waifish Alyson Hannigan for the “real” show wasn’t enough to elicit much more than a resigned sigh.)

Books were worse. Even before I knew phrases like “male gaze” I was rolling my eyes over the endless litany of SFF heroines with an obsession for describing their cup size in extravagant detail. I didn’t think much about cup size as a teen, but I sure did think about my muffin top and double chin and bingo wings, and how it would be nice to once–just once–read about someone who had all of those and yet still saved the world.

Boys had it better. Not great, admittedly, but better. Weight in male characters can be a marker for the down-to-earth everyman (the Bilbos of the fantasy world), or can go hand-in-hand with power, both in the physical (Broadway from Gargoyles) and political (Londo Mollari, anyone?) sense. There’s certainly an argument about the limited roles fat guys are found in–comic relief, “the heavy,” older mentors–but at least more than one of them exists.

Fat chicks get Dolores Umbridge; the “toad-like” sadist, whose attempts at femininity and beauty are there to emphasize the horror of her perversion of the mother archetype embodied by “acceptable” fat characters like Molly Weasley. Ditto The Little Mermaid’s Ursula (anti-mother), or Discworld’s Nanny Ogg (mother). Don’t get me wrong, I love Ursula and Nanny as much as anyone, but I was thirteen and much too young to be trapped into an adult woman’s archetype. Meaning I would’ve loved someone my own age as well as build to look up to.

I got one, after a fashion, in 1995, when Terry Pratchett introduced Agnes Nitt. Agnes, like Nanny, is a talented witch … one whose primary talent–resistance to mental manipulation–is predicated on her hostile relationship to her own fatness. Agnes’ unhappiness with her weight has given her a split personality: Perdita X Dream, her “inner thin girl.” When Agnes loses control, such as when being hypnotized by vampires, Perditia takes over.

You can be fat (I guess), and you can save the world (once or twice), but gods forbid you be happy while you do it.

#

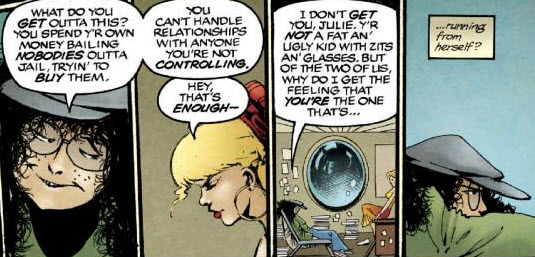

Around the same time Agnes Nitt was making her entrance on paper, MTV made an animated adaptation of Sam Kieth’s comic, The Maxx. It’s a semi-surrealist superhero deconstruction, and though it never quite got the momentum that the Frank Millers and Alan Moores of the world did, I loved it.

I loved it because of Sarah. Because, for the first time, I’d seen myself.

Sarah is a geek and a loser. She wore the same big, round glasses, the same oversized sweaters and shapeless jeans, had the same mess of un-styled (albeit curly) hair. She wanted to be a writer, like me, was standoffish and vulnerable, like me, and–most importantly–she was fat.

Just like me.

And yet, Sarah’s narrative arc doesn’t revolve around her weight. On her outsider status, yes, but she’s no Agnes; cast a skinny chick in Sarah’s role and her plot would be unchanged. Except Sarah wasn’t skinny.

She wasn’t helpless, either. Sarah is one of the protagonists, one of the characters who both moves the action and through whom the action moves. She’s flawed and imperfect, dealing with problems both mundane (depression, a fraught relationship with her mother) and fantastic (her father is a semi-dead rapist sorcerer who dwells outside reality). She’s lonely and angry and awkward, yet the narrative doesn’t deny her humanity or her importance. Sarah is, in other words, a hero in the context of the story in which she’s placed.

And, as a teenager, I identified with her. Hard. Because she was someone I knew I had the potential to be. Someone I wanted to have the potential to be, warts and all.

In the twenty years since I first saw Sarah, I can count on one hand how many times I’ve identified so hard with a fictional character. Sarah’s who I think about in conversations about diversity and representation, particularly when anyone dismisses the idea as unimportant. Because, thing is? If I hadn’t had a Sarah, I’d probably think representation was unimportant, too. It’s an easy position to take, not just when you’re so used to seeing yourself everywhere you don’t know what it’s like not to, but also when you’re so used to not seeing yourself that it doesn’t occur to you things can be so radically different when you do.

#

So. This is the part of the story where I’m supposed to tell you it gets better. Because I was a fat girl, into SFF, and I found my One True Representation, and it changed my life. That’s, how this goes, right?

Yeah. Right.

Thing is, it didn’t get better. I had Sarah and her rage and Agnes and her body hatred, and they were one of only a handful of characters who looked like me in an ocean of others who did not. Because there are no fat chicks in SFF, except for when there are. But how statistically insignificant does that number need to be before people will allow the hyperbole? We can test it, you and I. We’ll play a game. You name a fat woman from a videogame, comic book, fantasy, or sci-fi title, and I’ll name six thin chicks and a fat guy. Who do you think’s gonna run out of examples first?

I don’t have any answers here, no uplifting mortal. Only anger, and a rallying cry. I want more fat women in genre fiction. I want fat women whose narratives don’t revolve around their being fat, and whose fatness is not used as a lazy shorthand for mothers or for monsters.

I can’t turn back the clock and force things to be better. I can’t be a teenager again, watching the same shows and reading the same books, but this time finding them populated by big girls who laugh and love and fight and save the world. Whose big bodies are symbols of beauty and of power, not shameful obstacles to overcome. I can’t do that. But I can say there are girls out there now, girls with muffin tops and bingo wings and chunky knees, and they’re looking for heroes of their very own.

And I can ask you, oh fearless reader, what you plan to do to help them.

Alis Franklin is a thirtysomething Australian author of queer urban fantasy. She likes cooking, video games, Norse mythology, and feathered dinosaurs. She’s never seen a live drop bear, but stays away from tall trees, just in case.

Anne Frates

February 24, 2015 @ 10:04 am

there is a great fat girl proto type in Spider Robinson’s Callahan’s bar series. She’s fun, sexy, desired, and happy. Mary even plays a mean guitar. i seem to rememer another central plump female from an early Heinlein short story or two….

(edited, because, auto correct)

Cheryl

February 24, 2015 @ 10:20 am

This is why I play dwarfs in video games! Those models are usually larger than the human or elves so I can customize it to look somewhat like me.

The Circle of Magic series by Tamora Pierce includes a variety of body types among its characters. That plus many other things makes it one of my favorites.

S. Kay Nash

February 24, 2015 @ 10:33 am

There are a few more glorious fat chicks in comics and literature. Yes, they are hard to find.

Maggie Chascarillo from the comic, Love and Rockets. That was the first time I saw a character I could relate to. She started out as a stereotypically “hot” young woman, and she gained weight in adulthood. Her weight never stopped her from having adventures or being a kickass woman. Maggie was my fictional buddy for years.

There’s also a decent fantasy anthology edited by Lee Martindale called “Such A Pretty Face” published about fifteen years ago. You’d probably have to search the used books for it. I don’t think anyone has put together an anthology like it since.

Jim C. Hines

February 24, 2015 @ 10:45 am

I remember when Lee put that anthology together, but I never managed to get my hands on a copy. I need to remedy that.

dstarrw

February 24, 2015 @ 10:49 am

I am an older fat woman who once was a young fat girl looking it from the outside. And there was no one at that time like me in any of the stories. Fat was generally used as a short hand to mean lazy, stupid, gross and/or evil.

I try to support writers who bring diversity to the table and I still don’t see fat women as any heroes. This was an exciting column to read because I thought here is someone who really gets it. I went over to her website. I can’t begin to tell you just how disappointed to find out that her books are about gay men.

bluestgirl

February 24, 2015 @ 10:54 am

This made me think of a recent essay in The Butter, “This is an Essay About a Fat Woman Being Loved and Getting Laid.” It’s not SFF, but it blows my mind every time I read it.

Beth Wheeler

February 24, 2015 @ 11:08 am

There is a copy of that anthology on Ebay even as we speak.

Nina from the Young Wizard series by Diane Duane is another good character — plump, not pretty, but one of the more heroic I’ve read in YA.

Lenora Rose

February 24, 2015 @ 11:09 am

First: Don’t judge a writer’s output by their first and sole series being worked on. She’s clearly early in her career. I know that, depending which book I first got published I could also come across as a “writer of gay men”. I’d hate to think someone would then shrug off my whole output as doomed to be just that.

Second: Unless you’ve read the books you don’t know who else shows up inside the text. I think it’s promising that the second book features a (fit, slim) woman on the cover even though it looks like a direct sequel with the same protagonist, because it’s the first step to being sure she’s trying for a variety of characters.

Lenora Rose

February 24, 2015 @ 11:12 am

It’s nice to see people listing examples — I can add Lori Ann White’s Etta Mae’s Little Theory to that if you can find an extant copy (our mutual publisher closed) — because it gives some more examples, but at the same time, I think it also kind of misses part of her challenge.

Pam Adams

February 24, 2015 @ 11:24 am

Sybil, Sam Vines’ wife in the DiscWorld series is a large woman.

I loved Such a Pretty Face- it’s on my shelves somewhere.

Lee Martindale

February 24, 2015 @ 11:34 am

When Meisha Merlin went under, I acquired as many of the remaining copies as I could. I have copies of the trade paperback and limited edition hardcovers available at HarpHaven.net. Both are also available through Amazon.com, although copies of the trade paperback are low and will be replenished as soon as I get back from this weekend’s convention.

Chrysoula

February 24, 2015 @ 11:42 am

Fat young woman. I can do this one.

I found Agnes a weird character in Pratchett’s roster. I think it was precisely because she was unhappy all the time. So. Fat young woman who isn’t defined by it. Check. I can _do_ this.

Claudia

February 24, 2015 @ 11:47 am

Having been a fat geek girl all my life, I can say with absolute certainty that I now just accept (and to some degree internalize), the fact that I won’t be represented in SFF. By internalize, I mean that reading this, I agree with everything you’ve said, but at the same time my brain is dinging me with the following: “well of course there aren’t fat chicks in SFF… I mean, in SF you have to fly around in spaceships and normally you have to be athletic to be part of that. I mean Starfleet was a military organization, and there are pretty strict fitness standards even in today’s military. And Fantasy? In epic fantasies people walk for miles in a day just to get anywhere, why would they be fat? There’s no room for someone of my body type in either genre. How can you slay dragons when you’re fat?” (BTW, I’ve heard some people on the web say that Breann of Tarth in Game of Thrones is fat, but she isn’t… she’s not petite, but I’d say she’s athletic, and she’s not fat for her height).

I guess internalizing it is a little sad, to some. But I never really thought about it. That’s the kind of SFF I was raised on, so I got used to the fact that I’d never be the hero in those kinds of stories. I got used to those things ^ making “sense” and being “logical.” I got used to daydreaming that I could someday BE that thin. I got used to wishing, desperately, that I COULD cosplay Arwen or Galadriel, but instead will just have to be happy with cosplaying Princess Fiona or Ursula.

I’m 35 today, and way past feeling sorry for myself. And way way WAY past hating the body that nature or God or whatever you believe in, chose to gave me. I’ve been fat all my life. Fat baby, fat kid, fat teen, fat adult. I’m “healthy” fat, even though by the 1870s standard of BMI that we still use, I am obese. Even possibly morbidly obese. But I eat healthier than most thin people I know, and my vitals are perfect… so perfect that my doctor just shakes her head because it doesn’t make sense that I’m obese and healthy, I guess. I jog almost daily… yes JOG. I pay more for health insurance and life insurance. I pay more for clothes so I don’t look like a frumpy granny. I’m getting married next year and I am getting my wedding gown custom made, because what a pain in the ass to find something I like in my size and that doesn’t make me look like a house.

Last Halloween I cosplayed Jolie’s Maleficent with a handmade custom costume, and I won the office costume contest and everyone said I looked totally awesome. And I totally did, because I rocked it. But then I used the picture from that Halloween as my profile page on Facebook, so it’s what you see when I post on political or comment forums that use Facebook for posting. And I was rudely reminded that to a lot of people, Fat is still the last bastion of acceptable discrimination. People who disagreed with me (on politics, or even opinions on MOVIES, for Christ’s sake) felt that it was okay to make disparaging comments about being a “Fat Maleficent.”

At 35 I could give a shit what a troll on the internet thinks of my weight. I’m getting married to a wonderful, loving man who loves me for me. And more to the point, I love me for me. I have to. This is the only body I get, and no matter how many people on the internet feel the need to tell me to “put down the Cheetos” and lose weight (Cheetos are gross, can I have hummus for a snack instead please?), I’m not ever going to be slender.

I’ll never be an elf. And I guess I am beyond caring about that sort of thing. I enjoy well-written SFF regardless of representation, although I understand and support the need for better representation of all peoples in our genre. But at some point, especially at my age and after you’ve been fat all your life, you’ve got to ask yourself… why should I give a shit? Why should I expend energy being upset that there will never be an elf with my body type?

Thanks for the blog post. It was pretty thought provoking, and important, I guess, for younger people who still aren’t comfortable with their bodies.

Claudia

February 24, 2015 @ 11:58 am

Well not for nothing, but gay men need representation too. Like heavy women and POCs, gay people sorely lack heroes in SFF that represent them.

bluestgirl

February 24, 2015 @ 12:16 pm

Link didn’t work. Sorry!

Essay is at:

http://the-toast.net/2015/01/26/fat-woman-love-laid/

Dana

February 24, 2015 @ 12:23 pm

Thank you for writing.

A. Pendragyn

February 24, 2015 @ 12:26 pm

Same boat here! Same disappointment with Agnes but luckily I didn’t read about her until I was an adult or I totally would have internalized even more self hatred than I already had. And I used to read romances, so yeah. If there was a fat chick she was most likely a villain or the mother or needing rescue- I gave up on romances after a while because of it.

I am a writer, though not yet published, and when I first started writing (at about 10) I assumed I had to write the stereotypical hero as the protagonist. I didn’t even think to put “someone like me” into that role. Instead she was the one the Hero rescued. Then I hit high school and finally had an epiphany; fat girls can be heroes, orcs can be the good guys, fantasy doesn’t have to mean medieval England.

Thanks so much for sharing this, it is so very nice to get validation.

Sylvia McIvers

February 24, 2015 @ 12:30 pm

Terry Pratchett later did another fat girl in Unseen University. Glenda works in the Night Kitchen and her plot arc is low self esteem bec. poverty and not being a tall willowy blond. She think it over and decides to ignore the unwritten rule that fat girls don’t serve at the high table, and makes other changes in her life. Yes! Confidence! And diet is never mentioned in the book. OTOH, the beautiful slim blond is clearly an airhead, and relies on Glenda for advice. Glenda never loses weight, and doesn’t plan to. She’s busy having a life, dear.

Sylvia McIvers

February 24, 2015 @ 12:32 pm

In Circle of Magic, the redhead ™ does awesome magic when called fatty. Then she grows up a little, and wishes it wasn’t beneath her dignity to do stuff to nasty people who tease. In the next sereis, she’s still fat, but worried about income and independence, not weight.

Between Heinlein & the Darkover series, the Redheads are Notable trope hit the SF community hard.

Lynnea

February 24, 2015 @ 1:57 pm

First, thank you very much, Mr. Hines, for posting this on your blog, and another thank you very much to Ms. Franklin for writing this piece.

As a person who is a) looking down the barrel of middle age and b) has always been fat, I’ve found that representation of fat protagonists in fiction is even more important to me now than when I was a teenager. Unlike Ms. Franklin, I was the painfully shy and awkward kid who sat alone and read at lunch. But, very much like her, I naturally assumed I could never be the hero of my own story. The best I could hope for was the bumbling sidekick. There were books like Dragonsong and Dragonsinger that told me that girls could be heroes, but none of the girls I read about looked like me. It was not girl-ness that precluded my heroism, but rather fatness.

I didn’t come to a more contented place in my life until pretty recently, and that’s in part *because* I started seeing more diversity in fiction. And I’m afraid I have to take the opposite stance from the prior commenter, Claudia – I think positive representation of fat people still matters to an adult life. How people like me are viewed in fiction (especially SFF, where we can build a society that looks however we want) colours how society and I interact. Fat protagonists aren’t just good for the self-esteem of young adults, but also for encouraging society to view fat women as something other than evil, lazy, or just comic relief.

mjkl

February 24, 2015 @ 2:24 pm

Do you mean “Unseen Academicals”? Just put in a request at my library – sounds wonderful!

Beth

February 24, 2015 @ 2:35 pm

I keep Mary from the Callahan’s stories in a special brain-place and haul her out when I’m feeling put-upon. She’s hugely competent *and* sexy while being fat.

dstarrw

February 24, 2015 @ 3:27 pm

You know I really hesitated about posting because I was sure that I would get a response like this. No where did I say that I wasn’t interested in the book or that I wouldn’t buy it.

And if you look you will see that at this time, it is her only book. What I was trying to say was how disappointed I was after reading someone that I felt really got it to find out she didn’t write either of her her main protagonists as potentially a fat woman. A gay man cannot be a fat woman so there was no chance of them being one.

dstarrw

February 24, 2015 @ 3:28 pm

And not for nothing but I didn’t say they didn’t. I have read a lot of stories with gay men as the hero and still feel that they need more representation.

But except for the anthology that Lee Martindale did, I can’t recall ANY stories where the fat woman is the hero.

Sally

February 24, 2015 @ 5:25 pm

Yep, Mary is often praised for her size. And she’s super-competent, in a usually quiet way. When she does something splashy (say, the incident which causes the title of one of the books), everyone’s impressed, but not surprised.

Sally

February 24, 2015 @ 5:34 pm

The “About” section implies that Alis has seen a dead (or perhaps undead?!) drop bear. Just not a live one.

This is far more interesting to me than whatever size clothes she wears. 😉

Also “Fat Chick vs. the Drop Bears” would be a terrific story. Waifs would be flattened by the mighty critters, but they’d bounce off the adipose tissue. Fat chick with a cricket bat (possibly magical, from an Ashes winner) saves the continent.

MT

February 24, 2015 @ 5:54 pm

I completely understand. I completely understand that moment of “oooh, they’re…. awwww… they didn’t!”

There’s an issue that lingers for me in all this. Representation tends to get sidetracked into who is being represented. I do talks and I open with: I am talking today about my experiences as a gay, HIV positive, man of 42 years. But it does not mean I am representative of gay or HIV positive or male or age.

We have this… thing that pressures us to expect better representation than is reasonable. I know in my own community there is no consensus over any of the labels I use to identify myself, and yet every bit of writing MUST represent ALL aspects of that community… and it can’t. “That’s not MY brand of gay” is a tune I hear regularly.

Finding ourselves in our choice of entertainment is more often about what speaks to us. Diversity in writing, for instance, is great but it can STILL miss feeling like the reader is being covered. So it’s great that some one writes another under-represented group in the genre, but it doesn’t mean it’s the SAME. You wish them well, cheer them on… but miss your own stories.

MT

February 24, 2015 @ 5:56 pm

Oh and please let me know if I just did a mansplaining thing because I don’t think I did but I have to wonder.

dstarrw

February 24, 2015 @ 6:31 pm

I certainly didn’t see it as mansplaining just understanding my position. And saying why.

Which I agree with completely. This is what I felt said better than I can:

So it’s great that some one writes another under-represented group in the genre, but it doesn’t mean it’s the SAME. You wish them well, cheer them on… but miss your own stories.

Jim C. Hines

February 24, 2015 @ 6:50 pm

I would read the heck out of that story!

Jim C. Hines

February 24, 2015 @ 6:51 pm

MT – What would it take to get you to write something up for this series next year? 😉

Jessica Strider

February 24, 2015 @ 7:02 pm

Very interesting post. Seeing yourself reflected in books in a positive light and with the agency to affect the story is so important. A few years back Crossed Genres did an anthology called Fat Girl in a Strange Land, which I got in one of their kickstarter campaigns. Every story features a large woman as protagonist in an SFF context. It’s unfortunately going out of print this month.

http://crossedgenres.com/blog/fat-girl-in-a-strange-land-goes-out-of-print-217/

MT

February 24, 2015 @ 7:43 pm

Check FB. I just posted a link to something I just wrote. I’m puttering at it because it still feels far too… Well first draft.

And I worry that it’ll present the idea that I see, often. If I say I don’t think we’ll ever get full representation of everyone, somehow that’s read as stop trying. No. I think there’s a limitation but it’s not a barrier, if you see what I mean.

I need to work on it. But sure. If you like. I’ll futz at it for a while (like… rest of my life). I’ll keep a copy somewhere for you if you’re still interested next year.

HelenS

February 24, 2015 @ 8:13 pm

Huh. I don’t recall Nina ever being described as plump, though Kit was. She’s not a “stick of a thing” like Dairine, but I’ve always thought of her as on the thin side.

Claudia

February 24, 2015 @ 9:42 pm

They are out there, just rare. And it would be nice if there were more, certainly.

Lenora Rose

February 24, 2015 @ 10:05 pm

I was mostly stung because, as a fat woman who has at one book making the rounds starring a gay male (an unhealthily skinny one, too), I felt a pretty nasty sting that felt a lot like “Oh, she’s one of us – except she’s not.”

In a very personal way.

Claudia

February 24, 2015 @ 10:05 pm

Your point is valid and thanks for sharing. I think it’s a matter of individual needs and taste. I love myself and I could give a damn what anyone else thinks of my body, so I guess I don’t feel the need for affirmation by having my body type represented by a hero in a book.

But I get what you’re saying. Because the only representation of fat people in media is usually as funny and/or gross sidekicks or lesser characters, people tend to view fat people as slobs on first impression. I am most certainly well aware that the reason I had trouble finding a job in the entirety of 2013 was because I was a size 20. I had to work a bunch of crappy jobs for nearly a year at a temp agency to PROVE I was a great worker, and only then did the agency go to bat for me and land me an awesome job worthy of my skills, which is now a permanent position.

Back to media: I certainly cringe every time a new sitcom starring Rebel Wilson or the like shows up, because I know it’s going to be full of fat jokes. I don’t begrudge Rebel a paycheck, and I happen to think she’s talented, but I can’t stand watching most of her roles, because she accepts being the fat slob and makes the jokes herself. I am cringing about the upcoming Ghostbusters movie, because it has like three fat actresses. Sorry, as much as I love Ghostbusters and I love them having a female Ghostbuster team, if the trailer for this film has a single fat joke, I’m out. I won’t be buying a movie ticket. Period.

So I get what you’re saying, but I guess I’m more passionate about fat representation in visual media, because I DO think the Chris Farleys and Rebel Wilsons out there are only further encouraging this last bastion of acceptable discrimination.

PatriotBlade

February 24, 2015 @ 10:57 pm

I wasn’t always heavy. There was a time I thought I could be “pretty”. In response to the “walking for days” comment; I work my tail feathers off in a retail job (= on my feet for hours on end), and still can’t afford a car. So guess what? I walk (bike in good weather) to and from work. With asthma, bad joints (old sports injuries, which is why I have trouble being active now) and chronic fatigue as a result of health problems (I am also genetically predisposed to obesity on both sides of my family) that make it next to impossible for me to lose weight.

I didn’t share all this to make people feel sorry for me. I share this to make a point. Why the h-e-double-hockey-sticks can’t a heroine be “fat”? A recent picture on Facebook made me laugh, then it made me think. It encouraged people to be thankful they were fat, because “fat people are harder to kidnap.” Yes, I would be harder to kidnap because of my weight. I am also overlooked as less attractive than skinny-assp girls. I am overlooked at work because people don’t think I’ll be as strong as I am, because of my size. For some reason, fat people are considered stupid and lazy. I am neither. But in an emergency situation, because of all of these factors, I’m the one that is most like to not only survive, but be in a position to help others. Because I will be underestimated, I will be beneath the bad guy’s radar. I won’t be seen as a threat.

What they don’t know is that, before the things in my life that caused my weight gain, I studied self-defense; my dad is a firearms instructor, so I know how to handle and shoot many different types of guns; I have good aim when I throw things; I am often “clumsy” on purpose, though actually rather agile, despite my weight. I know how to work several different computer programs (definitely not hacker material, but still). I am smart. I am a good judge of people. I am good at puzzles. Why under the great golden sun can’t I be a hero?!

PatriotBlade

February 24, 2015 @ 11:04 pm

Sorry. This is because I just saw a comment that hadn’t when I was composing my first.

Yes, fat jokes are crude. But I find something beautiful about a person who is comfortable enough in their own skin to feel beautiful, sexy, and fat. I make the fat jokes myself, so that others won’t make worse ones, because I already stole their thunder. I laugh at myself, make myself the butt of jokes, to make others less likely to hurt me worse.

Megpie71

February 24, 2015 @ 11:10 pm

Fat girls of the Discworld – well, Pterry has done a few. There’s Agnes Nitt, and I watched her over the course of three books – diffident and uncertain as a minor character in Lords and Ladies; frustrated shading to furious in Maskerade (and I really felt betrayed by the end of that book – where it appeared she’d had the magic “lose weight” transformation after walking home to Lancre from Ankh-Morpork); and then still furious (and still fat, which was both reassuring and realistic), but letting the fury out a bit more in Carpe Jugulum. I agree, the Agnes/Perdita thing was a bit of a nuisance, but I tend to see Perdita (even if she is described as “the thin girl” inside Agnes) as being more the voice of Agnes’ anger than anything else – her entirely justified anger at the way the world treats her because she isn’t what they consider to be “the right shape” (it’s notable that it’s when Agnes is being Perdita that she’s able to perform a lot of physical feats she thinks she isn’t capable of, such as the handstand on the edge of the bridge in the Gnarly Ground). Agnes was considered overweight even for a social context where slender isn’t prized, and I feel she probably had a lot of anger buried underneath everything. Accepting her anger makes her more powerful, in a way.

Then there’s Sybil Ramkin (later Sybil Vimes). She starts as the archetypical upper-class spinster who’s decided to “be sensible about things” when she discovered all the Ramkin fortune wasn’t going to overcome her shape as a disincentive to marriage, and settled down to a life of near-exile with her pets (in this world, they’d be cats or small yappy dogs; on the Discworld, they’re swamp dragons). Then she meets Sam Vimes, and they fall into a romance based on friendship first (a more realistic romance than a lot of fictional romances). As Sam’s wife, she blossoms into a respected society hostess and the acknowledged queen of the Ankh-Morpork social scene, as well as being a valuable campaigner for the rights of social minorities such as the goblins.

There’s also Glenda Sugarbean (from Unseen Academicals), the head of the Unseen University Night Kitchen, and the less-attractive friend of Juliet (Glenda isn’t really described very well, except as being not-Juliet, and big-busted). Glenda is one of those plump girls who’s decided to deal with life by getting practical, and she winds up taking this to extreme levels. Unseen Academicals actually has a couple of good solid (in both senses of the word) female characters, since Madame Sharn is another woman (albeit a dwarf woman, which … alters perspectives a bit) who isn’t described as being particularly slender, either. Indeed, if we add in Verity Pushpram (whose physicality isn’t mentioned except she has what could best be described as the opposite of a squint), the book has more women with speaking parts who aren’t living up to the expected standards of beauty for their respective species than women who are. (Mrs Whitlow, the Unseen University housekeeper, is definitely not a thin woman, although she’s one of the ones whose weight is used as a comedic element throughout the books – indeed her size gets its most complimentary treatment in The Last Continent.)

I’m not sure whether it’s stated explicitly in the text, but I tend to think of Tiffany Aching’s friend, Petulia Gristle (aka “the pig witch”) as being on the plump side, too.

Kanika Kalra

February 25, 2015 @ 4:05 am

You have no idea how much I can relate to this post.

When I was about eleven, I watched Beauty and the Beast, and I loved Belle’s character. Here was a Disney princess who was brave, bookish, intelligent, and perceived as ‘odd’. For the last three traits, I related to her, and for the first one I admired and idolized her. But, even then, there was one thing that made me sad: for all that people called her odd, she was thin and beautiful. It made me resign myself to the fact that I will never be as awesome as Belle, because unlike her, I have a muffin top.

When I read Eleanor and Park and saw a fat teenage girl who read comic books, dressed oddly and still managed to find an amazing guy, it made me happier than I can describe. But, Eleanor didn’t belong to SFF, my favourite (and I’m being mild here) genre. She had a mundane life, and she lived a broken existence. When she did get attacked in her ‘real’ setting, she let Park fight her fights. Then she cried in the bathroom. Eleanor was a wonderful character, and a great reprieve from the cliched female characters in YA Romance, but she was not awesome. She was not someone I could aspire to become.

When I read Magic Ex Libris, I felt ecstatic. Lena Underwood is neither obese, nor teenaged. But she is chubby, something that is thought to be not very different from ‘fat’ in our society. And she is not a mother figure, but a strong, healthy nymph who can kick some serious ass, and do it better than the male protagonist of the book.

In the new Who series, I liked Donna’s character for a similar reason. Sort of. She’s not fat, but she’s not stick-thin either. (Of course, her sass was the icing on the cake.)

SFF needs more fat heroines, and it needs them NOW.

However, like Claudia has pointed out above, fat chicks – the ones that are well and properly overweight, like me – can’t really run around kicking ass and saving worlds. That’s where my problem with Harry Potter comes in. J K Rowling once said that she loved the idea of witches and wizards because it shows that if you eliminate the factor of physical strength, women can fight just as well as men, and in some cases better than them. They don’t get side-lined in battles. Weilding a wand has nothing to do with your physical state. Why couldn’t we then have a fat female teenage character? A fat Luna? A fat Hermione? A fat Ginny? At least one of them?

So, yeah. Maybe Sci-fi can make its excuses about not having over-weight female protagonists, but Urban Fantasy cannot. Especially books that involve fighting with magical skills. This is one aspect of representation that I’ve never read an article about. At least, none that made me go, ‘Yes, this. Thank you for saying this!’

Now, I have. Thanks a lot, Alis, for writing this. And thanks, Jim, for sharing it with us.

Kanika Kalra

February 25, 2015 @ 4:24 am

I was planning to leave /another/ long comment, but then I read yours. This covers EVERYTHING I want to convey.

I am fat, and even though I might start panting if I ran up three flights of stairs, I can hold my own in hand-to-hand combat. And I don’t understand why people are surprised by that. Upper body weight does give you an advantage, and I have strong bones on top of that. These people have obviously not seen Po in combat.

I might not know how to use a gun, but I do have good aim, as opposed to what people assume. I love my body, and I have made plenty of boys in primary school sorry for teasing me, simply by beating them at arm-wrestling In front of their friends.

So, I think that, if I were not afraid of large animals – which has nothing whatsoever to do with my own body size – I could make a great SFF heroine.

In short, AMEN to whatever you said!

Beth Wheeler

February 25, 2015 @ 9:15 am

Someone called my memory of the Young Wizard series to account, and though I remembered Nina as being plump, it’s possible that she isn’t.

So I will substitute the delightful Nan from Diana Wynne Jones’ “Witch Week” instead. Nan is overweight, dreads gym, and is teased by the other kids (for multiple reasons, weight being one of them) — and is absolutely essential to correcting the imbalance in the world caused by an improperly split alternate world, due to her gift for story telling.

Meredith Putvin

February 25, 2015 @ 9:15 am

Check out Mercedes Lackey’s Heralds of Valdemar. There are many instances of same-sex characters within her books, most notably Herald-Mage Vanyel and Healing Adept Firesong.

Also check out Sherrilyn Kenyon’s “The League” Series. Notably “Cloak & Silence” though the main characters also appear in other books in the series as well. Maris in particular has to deal with the how his own family receives him, being disowned and all.

There have been plenty of books I have read that have been where the fat girl managed to turn herself around. The only one I can recall where the Heroine had serious personal image issue was “The Mirror of her Dreams” by Stephen R Donaldson. Otherwise the only place I’ve really seen it portrayed is satire and role-players trying to break stereotypes. There was one character a wizard in the Pool’s of Radiance novel (RPG/CRPG) that uses a wish spell inadvertently to be stronger (Be careful want you wish for). Only the wish made her look like a fighter and for a long time into the book she felt she was grotesque. It wasn’t until the Cleric she was working with showed her otherwise that she realize the spell. Goes to show that even healthy females can have body image issues.

dstarrw

February 25, 2015 @ 10:19 am

I feel that comes from misreading my comment. I was expressing my disappointment that someone who seemed to get how I felt so often didn’t take the opportunity to address it in her own writing.

I believe in diversity and want to see everyone represented. I read all over the spectrum. But it is hard enough to find strong, complete women characters (though much easier these days) much less a fat one. And I was disappointed – it actually surprised me just how disappointed I was.

John G. Hartness

February 25, 2015 @ 10:20 am

I love this essay, and applaud you for speaking your mind. Sometimes it doesn’t get better, and we have to learn to live with that. And it sucks, and I’m sorry. And you’re right, we of the community can do better, and we should. I’m only one dude, but I promise I’ll try.

dstarrw

February 25, 2015 @ 10:27 am

Thanks for alerting me to it. I also found the link didn’t work but got it through Amazon.

Tel

February 25, 2015 @ 11:00 am

Well, there was Massha in Robert Asprin’s “Myth” series. It’s been a long time since I’ve read it, but I recall she does get some happiness and saves the world while she’s at it. Unfortunately she’s probably the exception that proves the rule.

bluestgirl

February 25, 2015 @ 11:08 am

I have mixed feelings about the Rebel Wilson style fat joke. Because, in the movies I’ve seen her in, the fat jokes come as a sort of “taking the power back” attitude. Saying “I know you’re going to mock me for being fat, so I’m just gonna say it. I’m fat. So what?” I think the problem is more in the world where fat = mocked, than in that response to the world.

The other thing I tend to like about Rebel Wilson, when I’ve seen her, is that she never acts like fat is a source of shame for her, is anything to hide or pretend away. She (or the characters I’ve seen her play) has attitude and pride, and anyone who doesn’t appreciate her isn’t someone who’s worthy of her.

bluestgirl

February 25, 2015 @ 11:22 am

What I read in the original comment wasn’t “I thought she understood me, but turns out she doesn’t,” so much as “I thought I’d found the book(s) that would answer this need and it was a really exciting feeling, but it turns out I was wrong.” Getting one’s hopes up for sushi sucks when it turns out there’s lasagna instead, even though lasagna is totally yummy.

SherryH

February 25, 2015 @ 11:42 am

Alis, thank you! I’m a fat woman in my 40s, and though I was slim as a young girl, I don’t recall being any thinner than “plump” once I hit high school. In college, which was probably my peak physical condition, I could walk for miles (at a pretty good clip, at that), lift and carry just about anything, climb endless stairs, pretty much do whatever. And I was chubby, at the very least. (BMI said I was overweight to obese, but BMI is a crock…) And I was smart, if socially awkward. I could’ve been a hero!

But, alas, there were no hero “mes”. I don’t recall thinking too much about it, but it would’ve been nice.

I think the thing that bugs me worse than lack of fat women in stories and media is when there *are* fat women–and they’re caricatures, or the character is all about fatness, with no room in her life for anything other than fat and how she deals with it. Or the fat chick undergoes an “ugly duckling” transformation and becomes thin and beautiful. Ta-dah! Problem solved! Not.

Thanks for the very thought-provoking post, and keep on doing what you’re doing.

sistercoyote

February 25, 2015 @ 11:53 am

I just purchased a used copy from amazon. They’re at prices where shipping costs more than the book itself for the paperback, anyway.

sistercoyote

February 25, 2015 @ 11:54 am

Rather than Valdemar (which, unfortunately, has the “gay couples can’t have happy endings trope in spades), I’d suggest Lynn Flewelling as an author to look for. And Ellen Kushner.

sistercoyote

February 25, 2015 @ 11:59 am

Alis,

Thank you for this post. It’s nice to know when one isn’t alone, though I didn’t have The Maxx to comfort me as a young girl.

Weirdly, while thinking about this post and some related facebook shenanigans, I remembered that when growing up I wanted to be Lady Kluck from Disney’s Robin Hood (since I couldn’t be Robin — wrong gender — and I’d never be Maid Marian — too plump, even as a kid) because she was a bad ass who ran down rhinos like a football tackle and was unashamedly herself.

All of which made way more sense in my head.

Claudia

February 25, 2015 @ 12:49 pm

I read Valdemar, and didn’t really care it due to the fact that the gay couple never get their happy ending. Their life always seems to be one unhappy event after another and ends pretty poorly.

Thanks for the suggestions, though.

Claudia

February 25, 2015 @ 12:53 pm

You’re right about Rebel and her lack of shame for being fat, we need more of that, and that’s why I like her. But I cringe because the only roles they seem to want to give her, especially of late, is the funny fat slob.

Like, I hate The Big Bang Theory for the same reason… people seem to think that nerds and geeks should embrace the fact that TBBT brings geekdom into mainstream, but TBBT is laughing AT geeks and nerds… mocking them.

Rebel’s last attempt at a sitcom, which was very short-lived, as a train wreck. It was terrible. Unfunny with copious amounts of fat jokes. I saw the pilot and I was out, and completely unsurprised it didn’t survive the entire season. I don’t even remember the name of that sitcom.

I just feel like Rebel should be given better roles than that.

Claudia

February 25, 2015 @ 1:01 pm

I respect your POV, but I can’t do it. And I don’t like it when others do it to themselves. Self-deprecating humor is ultimately still hurtful to the individual.

My friends don’t make fat jokes around me, and I don’t make fat jokes either. It’s because they respect the hell out of me, and I respect the hell out of my self. I’m perfectly comfortable in my own fat skin, and I dress better than some much skinnier women I know. Hell I’ve TAUGHT skinny friends how to shop for clothing that compliment their physique. So there is nothing to joke about when it comes to my body. It’s just my body, and people can either accept that or not. I accept it. There’s no reason to discuss it further, which includes telling jokes about it.

Just how I feel, personally. I’ve never been a fan of self-deprecating humor of any sort.

Claudia

February 25, 2015 @ 1:05 pm

Your point about Belle is interesting, because it always bothered me that in the initial song for the film, when she’s walking through that provencial town, the townspeople sing about how beautiful she is, and that it’s a shame that such a beautiful girl is weird and reads books. But they still accept her in their midst.

Because it made me realize that her beauty is the only reason they tolerate her weirdness. If she were butt-ass ugly and fat, and also a bookish nerd, they would have turned her away. At least that’s my interpretation of that song.

Don’t get me wrong, Beauty & the Beast is still one of my favorite Disney films. But yeah, that struck in my craw from a young age, and I still think about it sometimes, because I intimately know every lyric from that movie’s soundtrack.

Claudia

February 25, 2015 @ 1:08 pm

I hate the way fat people are portrayed in media. I was just having a discussion above with someone about the talented Rebel Wilson always being cast as the fat funny slob, and how I cringe at the potential for all those fat jokes in the new Ghostbusters.

The only thing I can think of where they turned the “fat chick gets turned beautiful (read: thin)” trope on its head is Shrek. When Fiona takes on her love’s true form, she turns into a fat ogre. She calls herself ugly, but then Shrek tells her she’s not, and she apparently comes to accept her new form.

Claudia

February 25, 2015 @ 1:10 pm

Kluck was great, but she was still just the sidekick, and I feel like that’s the problem. We’ve come really close to awesome, in rare cases being the fat but able/awesome/funny sidekick. But the hero in some epic? Ehh.

Kanika Kalra

February 25, 2015 @ 1:23 pm

Yes, I agree. I re-watched the movie recently, and it was that very first soundtrack that reminded me of the first time I had watched it and how I had felt. Even eleven-year-old me realized that Belle’s oddities were tolerated by the townsfolk merely because she was beautiful. Had she been fat and buck-toothed, they would’ve probably thrown her in the asylum with her father, and done it much sooner.

sistercoyote

February 25, 2015 @ 1:28 pm

Yes, exactly; I agree.

Lynnea

February 25, 2015 @ 1:49 pm

I’ve never seen anything Rebel Wilson has been in except Ghost Rider (where she had about 2 lines), so I can’t comment on her specifically. But, on a more general note, I have an issue with fat people using fat jokes.

I’m not talking about saying “yeah, I’m fat, brilliant observation,” which to me is reclaiming the word “fat” and working to disempower it as an insult. But telling fat jokes, or playing to stereotypes of fat people, is problematic.

First, if a fat actor isn’t writing their own lines, then it does read as punching down for cheap laughs. But even in cases where they are more responsible for their own lines and characters, reinforcing those stereotypes, or telling fat jokes (such as those told by John Pinette in his standup), feels like the person is just buying conditional acceptance in society. Like “look, I’m willing to be the butt of your jokes, now will you let me play your reindeer games?” I wouldn’t say it’s worse than a skinny person making fat jokes, but I don’t think it’s really better. Any marginalized person playing to a stereotype is, to me, hugely problematic.

dstarrw

February 25, 2015 @ 3:43 pm

That is it exactly, bluestgirl.

Sally

February 25, 2015 @ 7:25 pm

A casual peruse of the self-published ebooks shows there are a bunch of BBW romances, where she gets the hot guy. Or sometimes the hot werewolf or vampire, because Twilight, and so it’s kiiiiinda fantasy?

Regular SF not so much, though at least some women in the bajillion “Chicks In Chain Mail” anthologies has to be a substantial lady.

Sally

February 25, 2015 @ 7:32 pm

It wouldn’t be so bad if the fat person wasn’t also gross. If they just were there, maybe cracking a few fat jokes, fine. But they always seem to be all sweaty and dirty, clumsy, cursing, sloppy eater and farting. Can’t there be a fat person who’s neatly dressed with manners? They can still comment on their own size, but enough with the gross-out.

Sally

February 25, 2015 @ 7:37 pm

Plus, in the post-apocalyptic food wars, you’re going to survive better than all those skinny weak models. Particularly if it’s a nuclear winter scenario. You’ve got your fat to keep you warm and to live off of, and it’s good padding while you karate chop and shoot things.

bluestgirl

February 26, 2015 @ 12:43 pm

These are all really good points. I think I may be suffering from wishful-thinking-selective-memory. Because I’m remembering the good parts where I’ve seen Rebel Wilson portrayed as a desirable person, and not slobby or gross or anything, and the more I think about it, the more I remember “oh right that same movie also had THIS part,” etc.

Soooo… she gets some good parts? But clearly not as much as she deserves.

(I’m replying to everyone on this convo, but I didn’t want to over-nest the comment.)

Diana M.Pho

February 26, 2015 @ 3:13 pm

Tossing in another book rec: Half-World by Hiromi Goto (YA fantasy/horror). Melanie, the protagonist is an Asian-American heavy-set teenage girl who has to rescue her mother from this creepy limbo spirit world; the novel is sort of a feminist version of the Orpheus myth, and some of the imagery really stayed with me long after I read it.

Chris Dangerfield

February 26, 2015 @ 7:52 pm

Great essay. I feel the same way about being gay. All those young years of knowing I would never see my geeky gay self in SFF. Obviously, it’s not all the same as it was for Alis. Some things were harder, some easier. But reading Alis Franklin‘s words made me realize how giddy happy I am when I start seeing anyone not in the rigid sexual norm in any art-form. How much am I loving THE YOUNG PROTECTORS where a lead character is gay, but the storyline isn’t about his gayness. Or the fact that we’re looking toward seeing our first openly trans character on television. I cheer for Alis and her goals. It reminds me that we can all be incredibly different, but for those of us in any minority… we just want to see ourselves as the hero once in a while. Thanks for this excellent post.

Friday Links (harmful books edition) | Font Folly

February 27, 2015 @ 10:12 am

[…] ALis Franklin: Fat Chicks in SFF. “I knew, at the tender age of thirteen, that I would never be a hero because I was a girl, and I was fat.” […]

davidbreslin101

February 27, 2015 @ 11:44 am

Hm. Maggie from Love and Rockets was my only suggestion too. The starkest example of how differently fat is used to characterise men and women is probably George R R Martin’s early SF novel “Tuff Voyaging.” Tuff’s big beer-belly is part of his portrayal as an eccentric whose priorities are actually more down-to-earth than those of the more normal people around him. Meanwhile, the first characters described in the book is a fat woman. My ears pricked up because, yes, this is a character description you rarely see in SF at all. Of course, she turns out to be greedy, treacherous, lazy, whiny and stupid.

Curvaceous Dee

March 2, 2015 @ 3:39 am

I got that anthology in ebook format. It’s absolutely excellent and I’m delighted I supported it!

Trina

March 6, 2015 @ 4:55 pm

They do get their happy endings though. Van and Stefan actually spend a few hundred years in the Forest of Sorrows, along with Yfandes, and when it’s time to save Valdemar again they go on to the Havens together. Seems happy to me. Plus, while Keren and her first lifebonded(Ylsa) didn’t work out she and Sherrill certainly did, and when ever they are mentioned they are shown to be pretty happy.

The five linkspam languages (6 March 2015) | Geek Feminism Blog

March 6, 2015 @ 7:49 pm

[…] Fat Chicks in SFF | Alis Franklin: “I don’t have any answers here, no uplifting mortal. Only anger, and a rallying cry. I want more fat women in genre fiction. I want fat women whose narratives don’t revolve around their being fat, and whose fatness is not used as a lazy shorthand for mothers or for monsters.” […]

lkeke35

March 6, 2015 @ 9:39 pm

Preach!

Lovely Links: 3/13/15 - Already Pretty | Where style meets body image

March 13, 2015 @ 7:14 am

[…] “There are no fat chicks in SFF. And by ‘SFF’ I’m including the broad tent of my teenage nerdish interests: sci-fi and fantasy novels and TV shows and films, yes. But also video games, comic books, trading card games, horror, urban fantasy, roleplaying games. The works. There might as well have been a great big NO FAT CHICKS sign hanging outside the entrance. And me, p….” […]

Anna Tschetter

March 13, 2015 @ 11:17 am

Bitch Planet and Rat Queens are two sci-fi/fantasy comics that have fat women AND women of color. And they are amazing!!

Crane Hana

March 19, 2015 @ 8:41 am

Thanks to Alis and Jim, for this essay. I was a plump teen girl who became a plump woman. I have physically demanding day jobs and I work out – but I’m never going to be a size 12. I’ve also read SF&F for four decades.

The first time I read a size-positive portrayal of a fat woman in SF&F was in the mid-eighties, in one of the Alan Dean Foster ‘Icerigger’ sequels. Great space opera. The young, handsome, and hapless male hero rescues a stranded tycoon and his very fat daughter. The daughter is brilliant and fierce, ruthless and beautiful, the real power behind her father’s empire. She and the hero have some adventures and angst. They end up happily together when he realizes she’s the One.

Years later, I read Lee Martindale’s call-for-submissions for Such A Pretty Face, and realized I had an urban fantasy that might fit. It did, and I was honored that ‘The Blood Orange Tree’ was part of that groundbreaking anthology. I find it more telling that I was never able to find a decently-paying reprint spot for it; a year ago I gave up and put a slightly different version on my blog as a free read. (But please score the antho. I still have Lee’s buy links active, and the whole collection is marvelous.)

Gay in genre fiction is fashionable and cute now (I can say that, as a M/M romance writer). Non-white characters are no longer The Exotic Unknown. Fat people? We’re still comic relief, if we’re lucky.

Later this spring, I’ll have a high fantasy novel out on sub, featuring a very large swordswoman from a culture where she’s considered a bit too thin. We’ll see how it goes.